Healthy Cognitive Aging in the 21st Century: The 2nd puzzle piece to the Successful Aging Concept

Given the fact that our aging population increases as we speak, the concept of successful aging has been a topic of interest not only to researchers but also to society at large. According to the World Health Organization (2012), the number of individuals aged 60 and above in the world will have doubled by approximately between 2000 and 2050. In translation, the group of individuals over 60 years will have grown from approximately 11% to making up 22% of the whole world population.

Most studies though (Yaffe, Fiocco, Lindquist, Vittinghoff, Simonsick, Newman, Satterfield, Rosano, Rubin, Ayonayon, & Harris, 2009) and, with it, most information available to society, have focussed on physical functioning. Yet, while physical well being is an important part to successful aging, cognitive aging has now come to the forefront of society’s consciousness with more and more people surpassing current life expectancy and many reaching the 100-year mark (Temple University, 2013). With it, worries about dementia are increasing as well, at an individual as well as societal level, because dementia is considered an “aging-dependent disease”. In other words, the risk of developing dementia (e.g. Alzheimer’s Disease) increases sharply as we age, with 25-35% of people aged 85 and older having dementia or experiencing cognitive decline (World Health Organization, 2012). Given the increasing proportion of older adults in the world population, this also means that people experiencing cognitive decline or dementia will become more prevalent.

In combination with the financial re-structuring of society, requiring people to remain in the workforce due to later and later retirement, dissemination of such knowledge can be easily misunderstood and thereby bolster ageism (see, for example, Mann, 2010). For example, the motivation to hire older adults may be curtailed by fears created by misconceptions about the aging process. The consequence of such misconceptions can lead to unwillingness to hire older workers due to fears that older adults may suffer dementia and therefore may not be able to perform when in actuality older adults can bring a wealth of information and wisdom to a job. Moreover, while health researchers have suggested that ageism results from misconceptions about the aging process, the consequences of such misconceptions can also be detrimental to the healthy aging process (Minichiello, Browne, & Kendig, 2012). Importantly, while Alzheimer’s Disease is a brain disease that is associated with aging, research has shown that it is NOT an inevitable result of aging. It is therefore worthwhile to understand the difference between normal and pathological aging and learn about potential preventative strategies to support successful (or optimal) cognitive aging and reduce the risk of developing dementia.

Healthy versus Disease-Driven Aging

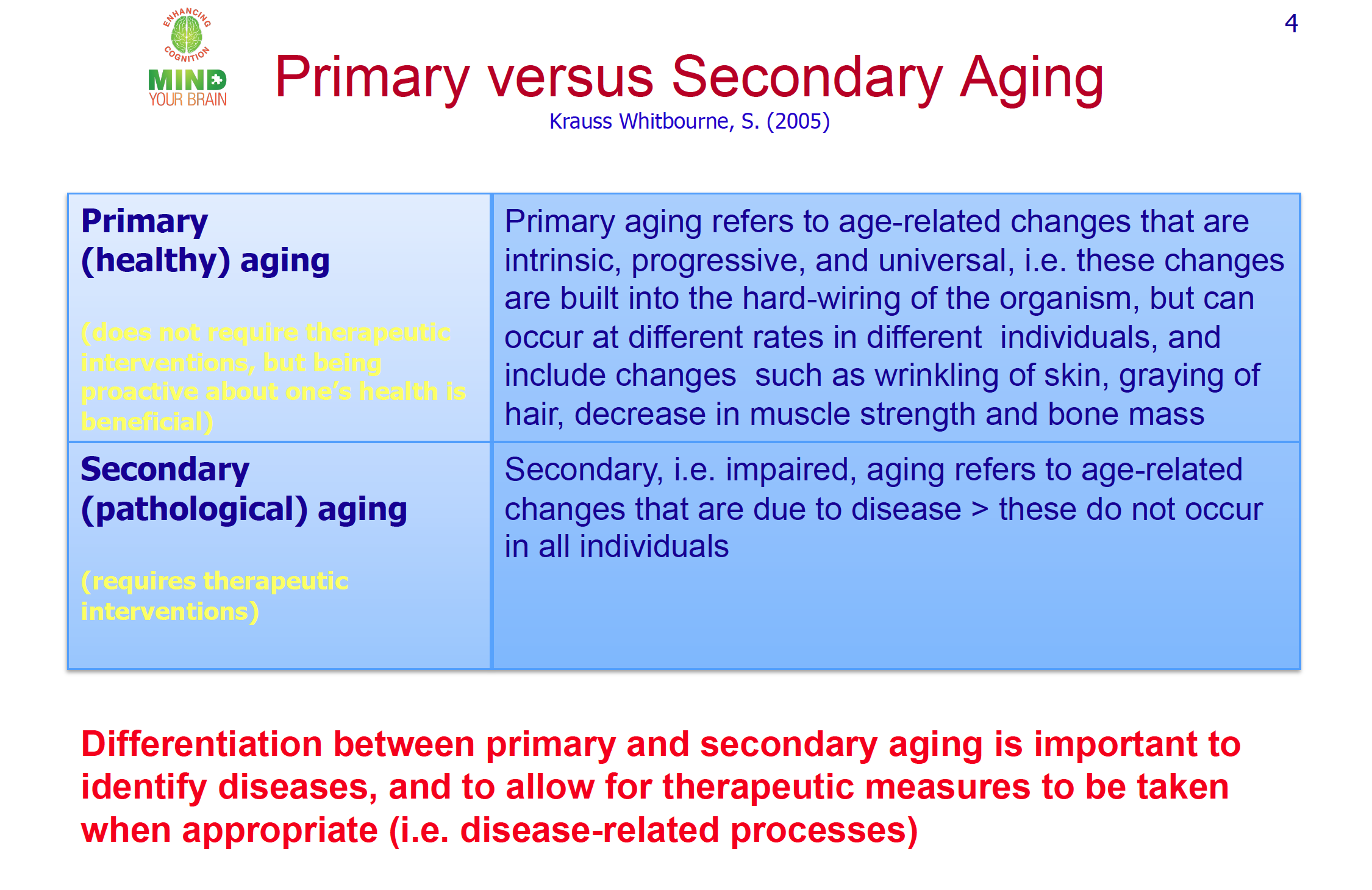

Normal (or primary/ healthy) aging refers to age-related changes that are intrinsic, progressive, and universal (Krauss Whitbourne & Whitbourne, 2011). In other words, these changes include the inevitable deterioration of structure and function that are built into the hard-wiring of the organism, and include such changes as wrinkling of skin, graying of hair, decrease in muscle strength and bone mass. Of course, and as anyone can easily discern by observation, these changes can occur at different rates in different individuals.

In terms of cognition (thinking ability including for example attention, information processing, reasoning) research has shown that healthy aging includes a balance between stable cognitive abilities and cognitive decline throughout the lifespan (Cognitive Skills & Normal Aging, n.d.; Salthouse, 2004). For example, some functions such as information processing speed (i.e. the speed with which we can process information) as well as the ability to maintain and manipulate information in our mind decline while others such as our verbal ability and knowledge store will improve with age. These cognitive changes, mentioned above (e.g. slowing of information processing speed), translate into everyday life experiences such as ‘losing one’s train of thought’ more frequently and difficulties retrieving information (also called tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon) or remembering new information. However, while cognitive decline may be inevitable for some cognitive components (i.e. processing speed) as we age healthily, these suggested changes will not interfere with successful functioning in everyday life.

If such cognitive changes include greater difficulty than for others of the same age and level of education in domains such as short-term memory and reasoning, then a comprehensive clinical evaluation at a clinic specialized in aging or memory loss is indicated. Such evaluation will provide clarification as to the causal factors involved in the decline and help with prevention of further cognitive decline to a condition called Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI).

Although estimates vary widely with regard to the rate of progression from MCI to dementia, research suggests that at least some people diagnosed with MCI will progress to Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Importantly, however, a diagnosis of MCI does not necessarily lead to a diagnosis of AD down the road (Mitchell & Shiri-Feshki, 2009). When MCI does progress to a diagnosis of dementia, it is considered pathological aging.

Your can learn more about Dementia here: https://mindyourbrain.com.co/aging/what-is-dementia/

Pathological (or secondary) aging refers to age-related changes that are due to disease processes that will eventually interfere with successful daily functioning. Again, these changes are physiological changes that are NOT inevitable, and thus they do not occur in all individuals (Krauss Whitbourne & Whitebourne, 2010). As a consequence and in contrast to healthy aging processes, pathological aging processes do require therapeutic interventions. For this reason, it is important to differentiate between these two (healthy versus pathological aging) – not only to allow for therapeutic measures to be taken where appropriate but also for the development of preventative measures.

In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has called into action “The Healthy Brain Initiative: A National Map to Maintaining Cognitive Health” whose primary actions include an emphasis on primary prevention (http:/www.cdc.gov/aging/healthybrain/roadmap.htm).

Successful/ Optimal Brain Aging

In general, optimal or successful aging refers to the way an individual can alter people’s aging processes by engaging in preventative measures and compensatory strategies. Utilizing such techniques permits an individual to avoid the negative changes that occur with pathological aging and slow down the normal aging process. More than likely, you will have heard that regular physical activity (Booth, Laye, & Roberts, 2011) and a healthy diet are not only beneficial for physical health but also for cognitive health.

However, revolutionary to the study of lifespan development and cognition is the fact that the brain retains its plasticity – its malleability -, and thereby its ability to change itself throughout the lifespan (Thornton, 2011). As a result, we continue to have options throughout our lifespan to support our brain to change and thereby to support healthy and successful cognitive aging.

What can be done to support optimal cognitive aging beyond following a healthy lifestyle (e.g., physical activity, healthy diet, use of stress reduction techniques, ensuring enough sleep)?

Well, to keep your cognitive abilities such as memory, attention, and thinking speed at optimal levels, you can complete complex cognitive activities and exercises, or, in other words, exercises that will engage your brain and cognition actively. So, if you are doing cognitive activities where you have to really concentrate and think things through, then you are on the right track! Examples could include doing your taxes, planning a wedding or any other get- together, taking a course on a subject you love, learn a new language or to play an instrument, or playing bridge or other games that require strategy development- the possibilities are endless on how a person can ensure mental stimulation.

Likewise, to gain the most benefit from completing cognitive exercises such as Sudoku, puzzles, or utilizing websites such as Happy Neuron, Lumosity, PositScience, CogniFit or BrainSpade (if you like such brain/ cognitive exercises), these activities need to be challenging to you- they must be neither too easy nor too difficult for you to complete. As well, cognitive exercises and activities will provide you with the most benefit if you do them consistently and regularly.

In addition, utilizing cognitive strategies such as paying close attention and actively processing new information (e.g. taking additional time to remember someone’s name after being introduced or using mental associations to permit recalling that person’s name later) can support people in keeping their cognitive abilities at healthy levels.

More information on how to support your cognitive health here

In closing, research evidence (Coyle, 2003; Middleton & Yaffe, 2009; Mental activity, brain health, and dementia risk- What is the evidence, n.d.) to date suggests that people who regularly stimulate their mental faculties with complex mental activities will be on average

More likely to maintain and improve their cognitive functioning

More likely to maintain and improve their cognitive functioning Less likely to show aging decline in their mental abilities and

Less likely to show aging decline in their mental abilities and Less likely to develop dementia

Less likely to develop dementia

Remember: Your brain matters. Therefore, Mind your Brain by challenging it!

References

Albert, M.S., DeKosky, S.T., Dickson, D., Dubois, B., Feldman, H.H., Fox N.C. et al. (2011) The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 7 (3), 270–279.

Booth, F., Laye, M.J. & Roberts, M.D. (2011) Lifetime sedentary living accelerates some aspects of secondary aging. Journal of Applied Physiology, 111, 1497- 1504.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2007) The Healthy Brain Initiative: A National Public Health Road Map to Maintaining Cognitive Health. Retrieved March 31, 2013, from http:/www.cdc.gov/aging/healthybrain/roadmap.htm

Cognitive Skills & Normal Aging (n.d.). Retrieved April 1, 2013, from http:/med.emory.edu/ADRC/healthy_aging/healthy_aging/index.html

Coyle, J.T. (2003) Use or Lose it- Do effortful mental activities protect against dementia? The New England Journal of Medicine, 348 (25), 2489/90.

Krauss Whitbourne, S. & Whitbourne, S.B. (2011) Adult Development and Aging-Biopsychosocial Perspectives (4th ed). Hoboken, N J: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Mann, D. (2010, November 12) Aging workforce means dementia on the job could rise. Health.com Retrieved March 30, 2013, from http:/www.cnn.com/2010/HEALTH/11/12/health.dementia.rise.job/index.html

MCI Fact Sheet: What is MCI?, (n.d.), retrieved June 1, 2013 from http:/med.emory.edu/ADRC/documents/fact_sheets/mci_fact_sheet.pdf

Mental activity, brain health, and dementia risk- What is the evidence (n.d.) Retrieved April 6, 2013, from http:/www.yourbrainmatters.org.au/brain-health-program/brain/mental-activity/what-is-the-evidence

Middleton, L.E. & Yaffe, K. (2009) Promising Strategies for the Prevention of Dementia. Archives of Neurology, 66 (10), 1210- 1215.

Minichiello, V., Browne, J., & Kendig, H. (2012). Perceptions of ageism: views of older people. In J. Katz, S. Peace, & S. Spurr (Eds.) Adult Lives: A Life Course Perspective (332- 338), Bristol, UK: The Policy Press.

Mitchell, A.J. & Shiri‐Feshki, M. (2009) Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia – meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 119 (4), 252- 265.

Salthouse, T.A. (2004) What and When of Cognitive Aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science,13(4), 140-144.

Temple University (2013, February 27). Study explores distinctions in cognitive functioning for centenarians. Science Daily. Retrieved March 30, 2013, from http:/www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/02/130227165126.htm

World Health Organization (2012) Ageing and Life Course- Interesting facts about ageing. Retrieved April 23, 2019 from http:/www.who.int/ageing/about/facts/en/index.html

Yaffe, K., Fiocco, A.J., Lindquist, K., Vittinghoff, E., Simonsick, E.M., Newman, A.B., Satterfield, S., Rosano, C., Rubin, S.M., Ayonayon, H.N., & Harris, T.B. (2009) Predictors of maintaining cognitive function in older adults -The Health ABC Study, Neurology, 72, p.: 2029 – 2035

Cognitive aging/ cognitive health

Cognitive aging/ cognitive health